The U.S. Government reports the financial condition of Social Security in its annual financial report. Social Security is included in the “Statement of Social Insurance,” which is reported after the main overall financial statements like the Statement of Net Cost, Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position, and the Balance Sheet.

The Statement of Social Insurance includes Social Security and Medicare. For both of these programs, the Statement includes calculations of the present values of future program receipts and expenditures, based on projections of future cash flows under current law and policy, and projected demographic trends.

The three groups include current participants who have reached eligibility age (retired people and beneficiaries receiving benefit payments), current participants that have not reached eligibility age (people working that are having payroll taxes deducted from their paychecks), and future participants (the young and the unborn).

For each of these classes of participants, the government calculates the discounted present value of future money projected to flow into the system, and the present value of future expenditures. From there, it subtracts the present value of expenditures from the present value of receipts, and arrives at a net present value for the overall program.

For Social Security, that net bottom line came to a negative $16.1 trillion in 2018, “up” from a negative $13.3 trillion in 2014. In other words, the financial position of Social Security deteriorated by almost $3 trillion over those four years.

You can see those amounts reported on the Statement of Social Insurance on p. 61 in the 2018 Financial Report of the U.S. Government. Social Security is in the top table in that Statement.

Take a closer look at the three different classes of participants, in that top Social Security table, and how they add up to a negative $16.1 trillion. Netting the present value of expected receipts and expenditures for the three classes separately, you end up with an even more disturbing picture.

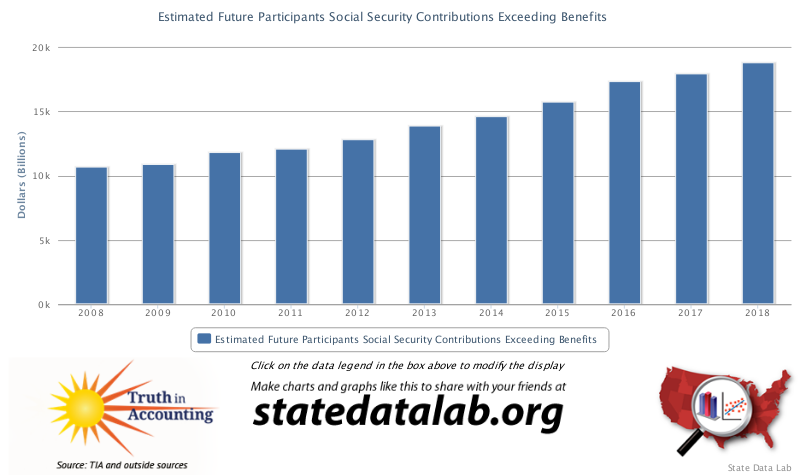

The massive $16.1 trillion overall hole for Social Security arrives despite a huge POSITIVE ($18.8 trillion) contribution to the program assumed to come from future participants!

What does this imply about the value of Social Security for the young and the unborn, if they are expected to provide a huge positive boost to current participants? Does this not imply a massive intergenerational welfare transfer, from future to current participants?

Note that the U.S. government chooses not to include the massive unfunded overall future obligations in Social Security in its balance sheet, under the reasoning the government can change the law at any time. At Truth in Accounting, we believe it should be included and reported as a debt under current law and policy, on the balance sheet, and then changed if and when the government changes the law (and the expected taxes and benefits).

In turn, we calculate the net positions of Social Security (and Medicare) using a “closed group” perspective, when calculating our assessment of the “true” federal debt. We do not rely on the cash flows assumed for future participants, for a few reasons. One of them relates to how the term ”future participants” can be thought of as an oxymoron – how can you be a participant in something you never had a choice (or a vote) to participate in?

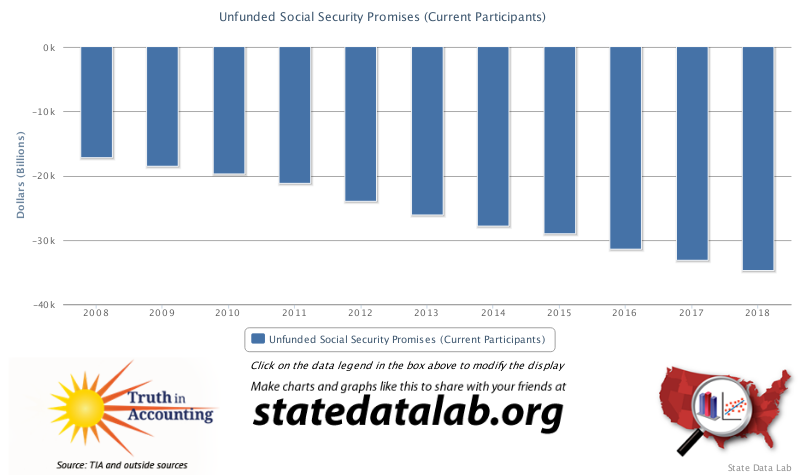

Here’s what we calculate for the net unfunded promises of the Social Security system, under this “closed group” calculation (that doesn’t count on future participants):

In turn, here’s what has happened to the net position for the program from future participants in Social Security themselves, over the past decade:

That massive and growing positive contribution from future participants does not imply good things for future participants themselves.